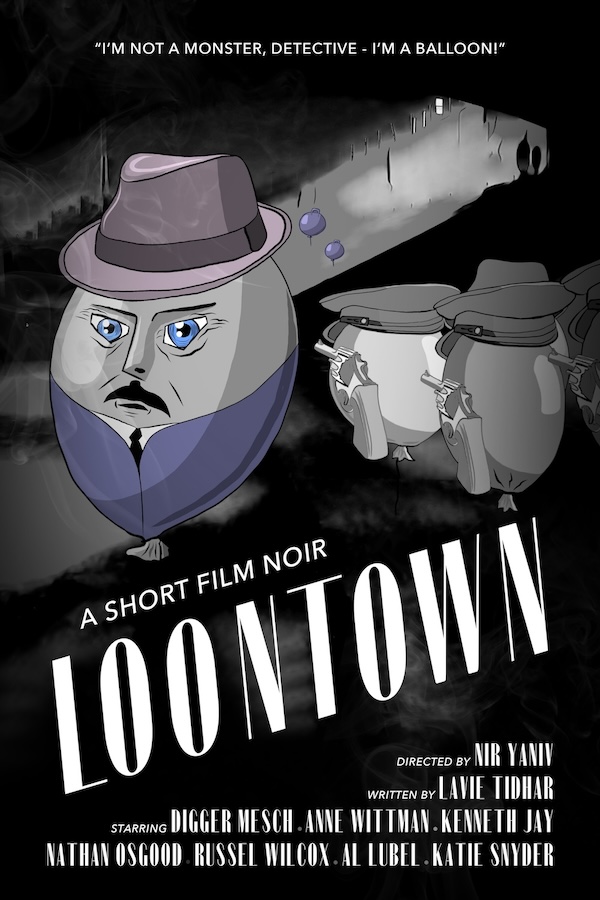

The new short film Loontown was released yesterday. Written by multi-award winning author Lavie Tidhar and directed by Nir Yaniv, here’s some info from the press release:

Imagine The Wire crossed with Who Framed Roger Rabbit, add a healthy dose of classic film noir, and you’ll come close to this absurdist sci fi fable about lonely balloons with big dreams. Picture Humphrey Bogart reincarnated as a balloon detective hot on the case of a missing shipment of helium (“street name H”), and this might be the movie for you!

When Mordy “The Mouth” is gruesomely – and literally! – popped in an alleyway, it’s down to world-weary detective Muldoon to solve the case. His quest quickly takes him up against a mysterious gangster just out of prison (a “twelve stretch in Blimpsville”), a seductive femme fatale named Red (who he helplessly falls for), and an inevitable meeting with destiny.

Filmed in and around Los Angeles, in locations including the famous alleyway from They Live and Chinatown’s LA River, the film mixes live action backgrounds with animated characters.

Here are the film’s credits:

- Written by Lavie Tidhar

- Directed by Nir Yaniv

- Starring Digger Mesch, Anne Wittman, Kenneth Jay, Nathan Osgood, Al Lubel, Russell Wilcox and Katie Snyder

As a long-time fan of Tidhar’s fiction, I am very much looking forward to watching this! I am also happy to share with you an interview with Tidhar and Yaniv…

*

What inspired you to create the world of Loontown?

Lavie: It was almost an Oulipo moment – you know, the literary movement that wanted to create new works using constraints. In our case, the constraint was technical – what shapes can we use as story vehicles within the limitations of what we can do? And it was going back and forth and I think in the end I said to Nir, almost in exasperation, well, can you do balloons? They’re basically just a circle! And Nir sort of said, yes, I can do balloons, and it was this light bulb moment – that, wait, this could actually be sort of brilliant.

So all the world and the internal logic of it and of the plot, the language itself, it all flows from that point onwards, that this is a balloon world, not a human one. Once we had that understanding, the story flowed very quickly from that.

Nir: To quote someone I deeply respect and admire: Yes, I can do balloons.

Can you describe the creative process behind developing the characters and storylines for Loontown? What were the challenges you faced in bringing Loontown to life as an animated film?

Lavie: So once the story was in place, and we had a script, Nir did what was really a game-changer for us, which is he shot a thirty second demo. And he hit on this idea of filming live-action backgrounds and settings, and having the animated characters interact in that physical space. So we had this demo shot in a bar in LA, with the background music that Nir composed, and the whole thing suddenly clicked – as soon as anyone watched the demo they instantly got what this was. So, great – we had a script, we had an idea of how we wanted to shoot it – what we didn’t have were actors, we didn’t have locations, and then the pandemic hit. So it wasn’t exactly ideal!

Nir: The idea for the demo shot hit me during a friend’s birthday party in a bowling alley in LA. There was a tiny bar space there, and the moment I saw it, a big balloon-shaped lightbulb popped over my head. So I took a few quick videos with my phone and later added a few random balloons and some synth sounds to give it the right mood. It looked nothing like the final film, but luckily its weirdness was enough to lure our actors in.

What role does humor play in Loontown, and how did you balance it with the other elements of the story?

Lavie: To me it’s very funny, because we play the film very straight. The comedy is in the world, but for the characters in that world the stakes are real. It’s not a comedy for them. So if you think of, say, a film like Girlfriend’s Day, which I love – the humor is entirely in the setup. Of course, in terms of the dialogue, that was just pure joy to write, with these hardboiled terms like “gasbag” or “skirt” all being terminology from the world of hot air balloons and so on.

Nir: This is a serious film about serious balloons who suffer through some serious trouble. I see no humor in it.

What are some of your favourite moments or sequences in the film, and why do they resonate with you?

Lavie: I’ve been struggling with that question a lot! I have to admit writing a sex scene for balloons was a particular highlight. It just made us both laugh so much. I love the piano player in the bar that Nir came up with. I love that moment in the opening when the first balloon appears and then turns and we see it has a face. I love the ending in the L.A. River. The locations Nir used are so iconic! Yeah, it’s hard to pick a favourite.

Nir: Associate producer Matan Mallinger and I spent days location scouting in downtown LA, looking for the right place to shoot the opening scene. Eventually, we found a trash-riddled alley, not far from The Last Bookstore, which had a perfect look and a somewhat less-than-perfect aroma. We shot about an hour of footage there, covering it from many angles. Only later we discovered that this very same alley is featured in John Carpenter’s They Live. Fun times!

Another favourite moment of mine is the very end, for which I asked actor Kenneth Jay to perform his part “like an Italian mobster version of Colonel Kurtz”. If you have no idea how that might sound, know that I didn’t as well. But Kenneth pulled it off in one go — brilliant!

And then, as Lavie mentioned, there’s the balloon sex scene. To augment Anne Wittman’s and Digger Mesch’s great performances, I bought some party balloons and rubbed them together in front of a microphone. I love SFX!

What are your future plans for the world of Loontown, and do you envision expanding it into other forms of media?

Lavie: I was playing with making a side-scrolling shooter game called Loonrunner. That was fun. But I find the technical element of making a game more interesting than having to try and then design thirty different levels. That’s hard work! So that’s still on the drawing board.

Nir: At the moment I’m being lazy, working on projects that don’t require so much live shooting. But hey, if Lavie gets a new and exciting Loontown-world idea, I’m game!

What was the most rewarding aspect of working on Loontown?

Lavie: For me, being only the writer, as it were, just seeing the whole thing come to life was sort of amazing. I’d get each scene as it was done, so I watched it in installments! And, of course, it’s very rewarding when lines you’ve written get spoken for the first time by the actors.

Nir: Hands down – working with the actors. Each and every one of them performed brilliantly, and the interaction was great. Many of their suggestions went into the final film. And after all the voices were recorded, I spent way too much time on sound editing simply because I was laughing so hard.

Do you have any advice for aspiring animators or filmmakers who dream of creating their own animated worlds?

Lavie: I’m biased, but I think you need a good story, first and foremost. It’s amazing how people can make movies on hundreds of thousands of dollars now, and the story just feels like it was written by an AI. On a napkin. At three in the morning. You’ve got to find the heart in the story first.

And then, I would say, you have access today to the most amazing technology, there are so many new ways of making animation. You can use a game engine, as many productions now do. You can do all kinds of things, and don’t have to necessarily aspire for a ten million an episode show. Do it with what you have, but do it for the right reasons, because it’s a story worth telling. I’d rather do something that looks crude and has a real soul than something that looks technically brilliant but has nothing to say.

Nir: The reason I’m able to create films at all, with almost zero budget, is an old technique called cutout animation. It’s essentially how all those old Monty Python animations were created: take an object, a drawing, or a paper cutout, and drag it across the screen. And viola! You have a film.

But this isn’t enough. Creating films is team work, even if the team is small and there’s hardly any budget. The way to create a film, of any kind, is to get some like-minded people to share the vision, and work together.

What are some of your favorite animated films, and what influences have they had on your work?

Lavie: So many. If there was one I was going to pick, in an “always trying to get more people to watch it” sort of way, it’s Tony Collingwood’s Rarg from 1988. It’s a short film, 23min or so, and I just adore it. It’s about these people who live in a sort of utopia who discover they’re living in a dream, then develop technology to break out into the real world to kidnap the dreamer and bring him back into the dream so he never wakes up – I can’t really do it justice. It’s both super fun, and a meditation on the nature of fantasy, the nature of escapism.

I loved a lot of recent animated shows: Green Eggs and Ham, Dead End: Paranormal Park, I love SpongeBob, of course. I love the Venture Bros. I love Sarah & Duck, which is a BBC animated show for children – I draw a lot of inspiration from the way it’s constructed, how the narrator interacts with the show.

Nir: I love animation in all its forms, but here I’ll mention one film that influenced me immensely when I started: Fantastic Planet, a 1973 French/Czech film. It’s weird, it’s beautifully drawn, the music is amazing, and it’s done in cutout animation. Highly recommended.

*

Loontown is out now. Check out the trailer, below.

Follow the Writer (Tidhar): Website, Goodreads, Instagram, Twitter

Follow the Director (Yaniv): Website, Goodreads, Instagram, Twitter