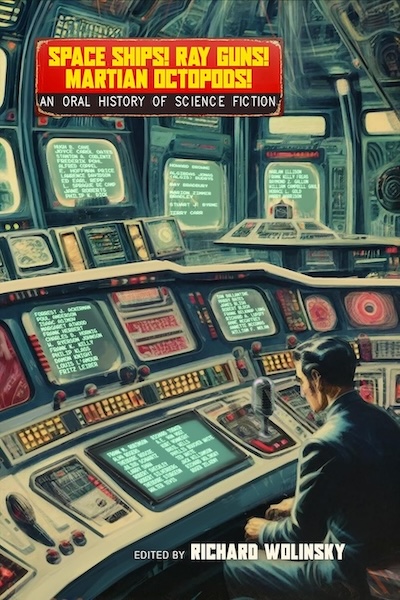

Next month, Tachyon Publications are due to publish Space Ships! Ray Guns! Martian Octopods!, an Oral History of Science Fiction, comprised of a collection of interviews with authors, originally conducted for the radio. The collection was edited by Richard Wolinsky, and is sure to appeal to aficionados of the genre old and new. The publisher has provided us with the introduction, written by Wolinsky, to share with CR’s readers. Here’s the synopsis:

Next month, Tachyon Publications are due to publish Space Ships! Ray Guns! Martian Octopods!, an Oral History of Science Fiction, comprised of a collection of interviews with authors, originally conducted for the radio. The collection was edited by Richard Wolinsky, and is sure to appeal to aficionados of the genre old and new. The publisher has provided us with the introduction, written by Wolinsky, to share with CR’s readers. Here’s the synopsis:

Today, depictions of aliens, rocket ships, and awe-inspiring, futuristic space operas are everywhere. Why is there so much science fiction, and where did it come from anyway? Radio producer and author Richard Wolinsky has found answers in the Golden Age of science fiction, between 1920 and 1960.

Wolinsky and his fellow writers and co-hosts Richard A. Lupoff and Lawrence Davidson, interviewed a veritable who’s who of famous (and infamous) science-fiction publishers, pulp magazines, editors, cover artists, and fans. The interviews themselves, which aired on the public radio, Probabilities, span over twenty years, from just before the release of Star Wars through the dawn of Y2K.

Probabilities was the home of a vivid cross-section of the early science fiction world, with radio guests offering a wide range of tales, opinions, theory, and gossip. It speaks to how, in the early days, they were free to define science fiction for themselves and push the genre to explore new ideas and new tropes in creative (and sometimes questionable) ways.

Space Ships! Ray Guns! Martian Octopods! is ultimately a love letter to fandom. Science fiction wouldn’t have survived as a genre if there weren’t devoted fanatics who wrote fanzines, organized conventions, and built relationships for fandom to flourish.

*

THE PROBABILITIES INTERVIEWS

Richard Wolinsky

Probably the most startling announcement any president ever made came on May 25, 1961 when President John F. Kennedy told Congress we would go to the moon before the end of the decade. At that moment, science fiction would no longer be the private playground of a small coterie of writers and readers. Now it had become part of everyday life for everybody on Earth. As a genre, science fiction quickly grew from a few books and magazines with a cult following into a pervasive phenomenon, accounting for thousands of literary titles and the most popular films and television shows of all time. By the end of the twentieth century, science fiction accounted for ten percent of all books published, and numbers two through five on the all-time box office list (Star Wars, The Phantom Menace, E.T. and Jurassic Park).

Science fiction had become reality because it was a literature of ideas and of speculation about what the future might be like. The fifteen-year-olds who read Amazing and Astounding magazines back in the ‘30s and ‘40s were now the scientists at Cape Canaveral and in Houston. The moon was not a mystery to them because they’d already been there in their mind’s eyes, reading the works of Heinlein, Williamson, Brackett and so many others.

It was no accident that one of the hotbeds of science fiction reading in 1945, according to circulation reports from the leading magazines, was Alamogordo, New Mexico, site of the top-secret Manhattan Project. Nor was it any accident that science fiction readers knew the names Werner Von Braun and Willy Ley long before they became famous for their work in the space program.

The first modern era of science fiction began in the 1920s, with the birth in 1923 of Weird Tales, often a repository of science fiction stories, and with the advent of Hugo Gernsback’s Amazing Stories three years later. The first era clearly ended that day in 1961, when John F. Kennedy made science fiction a reality and a mass phenomenon.

This book is devoted to that era, a time when the scientists and technicians who transformed the world began to read, to dream, and to imagine.

When Lawrence Davidson hosted the very first Probabilities program on KPFA-FM in Berkeley in February, 1977, that second era was just about to end. Four months later, Star Wars would hit the theatres and yet another era would begin. Science fiction would become fully integrated into our cultural life. Works of science fiction (along with those of its stepsisters, fantasy and horror) would be marketed as mainstream, and would rise to the top of best-seller lists, box office rankings, Nielsen ratings, even the Billboard charts.

A single science fiction shelf in a 1960 bookstore became a bookcase by 1970, three bookcases by 1980, and an entire wall by 1990. By the turn of the century, that wall might remain but in addition, we’d see works by Michael Crichton, Anne Rice, Doris Lessing, Gore Vidal, Caleb Carr, Walter Mosley and others sitting in a different part of the store, way in the front, among all the other best-selling authors.

Twenty-three years after its birth, Probabilities still exists, but it also has expanded into the mainstream, with a new title, Cover to Cover, and a list of interview subjects that runs the gamut from David Halberstam to Joyce Carol Oates, from Jim Lehrer to Scott Turow, from Lois McMaster Bujold to Dan Simmons.

In January 1977, Lawrence Davidson was the science fiction buyer for Cody’s Books, the legendary bookstore on Telegraph Avenue in Berkeley, California. He was approached by Padraigin McGillicuddy, Drama and Literature Assistant at KPFA-94.1 FM, the Pacifica Foundation’s flagship station in Northern California, to host a new science fiction interview program. The station’s last regular science fiction show had disappeared from the airwaves several years earlier, and Padraigin was casting about for a new one.

At the time, I was volunteering my services as receptionist and press assistant to the station. Lawrence, whom I’d known in New York, asked me to come to the station’s Shattuck Avenue digs with him and his two guests, up-and-coming writers Richard A. Lupoff and Michael Kurland, just to make sure everything functioned smoothly.

It’s a good thing I was there. Padraigin said she’d booked studio time, however the off-air studio was locked. She said an engineer would be waiting, but the place was deserted. The only person in the entire block-long warren of offices and studios was the on-air disc jockey, a red-headed seventeen-year-old named Kevin Vance. I flew into the control room and asked Kevin to unlock the studio and set up the tape. He quickly cued up an extended Bob Dylan cut, and together we ran down the hallway to the other end of the building where Lupoff, Kurland and Davidson stood in the dark. Kevin unlocked the door, turned on the lights, cued the tape, and set the microphones and sound levels. While the three participants waited, Kevin lectured me on how to engineer a program. “This is how you start the tape. This is how you stop it. Just make sure the meters don’t go into the red.” He fiddled with some dials while I looked on blankly. “Good luck,” he added, and disappeared into the darkness. I was alone, faced with half a dozen dials, a group of glaring meters, and three aficionados on the other side of the wall, yakking about the history of science fiction and how Gollum of Lord of the Rings was probably a Christ figure.

Somehow it all worked, and later that week Lawrence and I edited the tape for broadcast. By the second program, I had joined Davidson on the other side of the microphone. As a rabid science fiction reader, I was up on all the latest writers and trends. Davidson, on the other hand, was a pulp junkie. Ask me for a recommendation, and I’d say Dune or the latest Ursula Le Guin, or perhaps something by Phil Dick or Alfred Bester. Ask Davidson, and he’d talk about a story or book that had been out of print for thirty years. I was a child of the second era of science fiction, but Davidson was an atavistic throwback to the first. Fueling his obsession was a growing friendship with the older Lupoff, who had been reading the pulps since he himself was a kid in the ‘40s. The two of them would sit there for hours and discuss writers and editors only a handful on the planet would remember.

Thus it was no surprise that Davidson walked in one day with an ecstatic smile on his face. “I found Stanton Coblentz,” he said. “He’s living an hour outside San Francisco. Let’s go talk to him.” A beatific look came over Lupoff’s face. The Messiah had arrived.

“Who?” I asked.

And they’d patiently explain that Stanton Coblentz was one of the masters of ‘20s and ‘30s science fiction, author of gentle satires and a poet of note to boot. You should read him sometime.

Before long, Lupoff had joined the program on a regular basis. For every Coblentz that Davidson unearthed, Lupoff discovered a Frank K. Kelly. For every Ed Earl Repp that Davidson found lurking in Paradise, California, Lupoff retrieved an E. Hoffmann Price somewhere on the San Francisco peninsula.

Gradually over the course of several years, a history of science fiction in the middle of the twentieth century began to emerge on tape. Stuck in amongst the hoary old-timers were younger writers like John Varley, Elizabeth Lynn, Stephen King, Clive Barker, and younger editors like David Hartwell and Jim Frenkel.

By the mid-1980s, we’d spoken with many masters of the field, both writers and editors. As science fiction integrated itself with the cultural mainstream, so did we. The show took a different tack. Over time, Lupoff and I branched out into mysteries and Davidson gravitated to the Old West. By 1990, some thirteen years after we began, Davidson had left the show to pursue other interests (notably mountain-climbing), Lupoff was forging a career as a mystery writer of note, and I was a stalwart KPFA employee, editing the station’s monthly program guide/magazine. Though none of us lost interest in it, science fiction had become part of the larger world.

A decade later, the show is still on the air. Cover to Cover can now be heard in several cities via satellite, and on several websites over the internet. In the past few years, our guests have included Susan Sontag, Arthur Laurents, Tom Robbins, Norman Mailer, Gore Vidal, Molly Ivins, Helen Thomas. You get the picture.

For many years, the three of us have toyed with the idea of presenting these interviews in print. It was Frank M. Robinson who suggested the current form of an integrated oral history and has been enormously helpful in both vetting the contents and offering his sage advice. We chose to set the framework of the book between 1920 and 1960 because that was the first era of science fiction, when the field was largely unknown to the casual observer or reader.

Special thanks to Julian Francis Clift, who loaned me his transcription machine and saved time, money and effort in the process, and to KPFA’s Susan Stone, whose support has always been first-rate. Also to Patricia Lupoff, Tom Lupoff, Suzette Davidson, Bret Cherry, Jim Bennett, Jack Rems, and of course, to everyone who agreed to be interviewed and gave a little piece of themselves to our audience and to this book. We salute you.

*

Richard Wolinsky’s Space Ships! Ray Guns! Martian Octopods! is due to be published by Tachyon Publications in North America and in the UK, on August 5th.