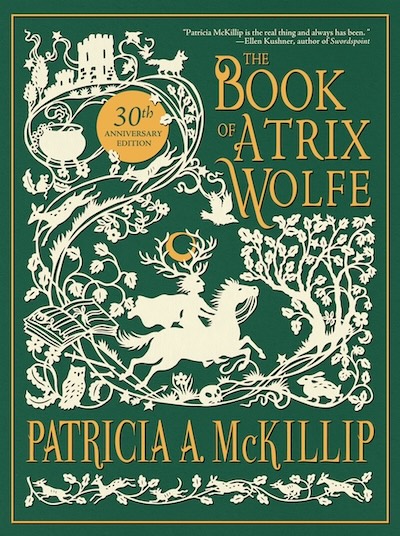

Next month, Tachyon Publications are due to release a 30th anniversary special edition of The Book of Atrix Wolfe by Patricia A. McKillip. To celebrate the release (on February 25th) and this milestone, the publisher has provided CR with an excerpt to share. Here’s the synopsis:

Next month, Tachyon Publications are due to release a 30th anniversary special edition of The Book of Atrix Wolfe by Patricia A. McKillip. To celebrate the release (on February 25th) and this milestone, the publisher has provided CR with an excerpt to share. Here’s the synopsis:

This brand new edition celebrates the 30th anniversary of a classic, luminous novel from the World Fantasy Award-winning author Patricia A. McKillip (The Forgotten Beasts of Eld). In McKillip’s stunning cinematic prose, the human world and the realm of faeries dangerously entwine through chaotic magic. Discover the spellbinding legend of generational atonement and redemption between a reluctant mage, a powerful wizard, a struggling heir, fae royalty, and a mysterious scullery maid.

When the White Wolf descends upon the battlefield, the results are disastrous. His fateful decision to end a war with powerful magic changes the destiny of four kingdoms: warlike Kardeth, resilient Pelucir, idyllic Chaumenard, and the mysterious Elven realm.

Twenty years later, Prince Talis, orphaned heir to Pelucir, is meant to be the savior of the realm. However, the prince is neither interested in ruling nor a particularly skilled mage. Further, he is obsessed with a corrupted spellbook, and he is haunted by visions from the woods.

The legendary mage Atrix Wolfe has forsaken magic and the world of men. But the Queen of the Wood, whose fae lands overlap Pelucir’s bloody battlefield, is calling Wolfe back. Her consort and her daughter have been missing since the siege, and if Wolfe cannot intervene, the Queen will keep a sacrifice for her own.

*

He had seen Pelucir in fairer days, when the massive, bulky castle stood surrounded by flowering fields, the slow river running under its bridge reflecting such green that drinking it would be drinking summer itself. The ancient keep, a dark, square tower beginning to drop a stone here and there, like old teeth, faced lush fields and meadows that rolled to a rounded hill where an endless wood of oak and birch began. Now the trees stood stark and silvery with moonlight, and on the fields a hundred fires burned in the burning cold, ringed around the castle.

The mage, still little more than a glitter of windblown snow, paused under the moon shadow of a parapet wall. Tents billowed and sagged in the wind; sentries shivered at the fires, watching the castle, listening. Wings rustled in deep shadow; a sentry threw a stone suddenly, breathing a curse, and a ragged tumble of black leaves swirled up in the wind, then dropped again. Another sentry spoke sharply to him; they were both silent, watching, listening.

The mage drifted past them, searching; dreams and random nightmares blew against him and clung. Within the castle, children wrapped in ancient tapestries wept in their sleep; someone screamed incessantly and would not be comforted; young sentries whispered of fowl browning on a spit, of hot game pie; old men trembling in the ramparts longed for the fires below, the sturdy oak on the hill. On the field, men feverish with wounds dreamed of feet made of ice instead of flesh and bone, of the sharp end of bone where a hand should be, of a mass of black feathers shifting, softly rustling in the shadows, waiting. The mage saw finally what he searched for: a flame held in a mailed fist on a purple field, the banner of the ruling house of Kardeth.

He had known rulers of Kardeth in his long life: fierce and brilliant warrior-princes who grew restless easily and found the choice between acquiring knowledge and acquiring someone else’s land an arbitrary one. Scholars, they spoke with equal passion of the ancient books and arts of Chaumenard, and of its rich valleys and wild, harsh peaks. This ruler, whose name escaped the mage, must have regarded Pelucir as a minor obstruction between Kardeth and Chaumenard. But while his army ringed the castle, laying a bitter winter siege, winter had laid siege to him. He had the wood on the hill for game and firewood; he had only to sit and wait, starving the castle into surrender. But there was nothing yielding about the massive gates, the great keep with its single upper window red with fire, the torchlit battlements spilling light and the shadows of armed warriors onto the snow. In the wood, the game would be growing scarce, and what remained of it, thin and desperate in the harsh season.

So the chilled, hungry, exhausted dreamers around the mage told him in their dreams. He took his own shape slowly in front of the prince’s tent: a tall man with hair as white as fish bone and a face weathered and hard as the crags he loved. He wore next to nothing and carried nothing. Still the guards clamored around him awhile, shouting of sorcery and warding invisible things away with their arrows. The prince pushed apart the hangings and walked barefoot into the snow, a sword in one hand.

The mage, noting how the prince resembled his red-haired grandfather, finally remembered his name. The prince blinked, his grim, weary face loosening slightly in wonder. Around him the guard quieted.

“Let him go,” Riven of Kardeth said. “He is a mage of Chaumenard.” He opened the tent hangings. “Come in.” He nodded at a pallet where a man, white and dizzy with fever, struggled with his boots. “My uncle Marnye. He was wounded last night.” He took the boots out of his uncle’s hands and pushed him gently down. His mouth tightened again. “They come out at night—the warriors of Pelucir. I don’t know how. They have a secret passageway. Gates open noiselessly for them. Or they slip under walls, through stone. At dawn I find sentries frozen in the snow, dark birds picking at them. My uncle heard something and was struck down as he raised an alarm. We could find no one. That’s why my sentries are so wary of sorcery.”

“There is no magic in that house,” the mage said. “Only hunger. And rage.”

He knelt by the pallet, slid his hand beneath Marnye’s head, and looked into his blurred, glittering eyes. For an instant, his own head throbbed, his lips dried, his body ached with fever. “Sleep,” he breathed, and drew the word into a gentle, formless darkness easing through the restless, shivering body. Marnye’s eyes closed. “Sleep,” he murmured, and the mage’s eyes grew heavy, closed. Sleep bound them like a spell. Then the mage opened his eyes and rose, stepping away from the pallet. He said, his voice changing, no louder, but taut and intense with passion, “This must stop.”

The prince, feeling the whip of power behind the words, watched the mage silently a moment. He said finally, carefully, “Thank you for helping my uncle. The ancient mages of Chaumenard do not involve themselves with war.”

“You are threatening Chaumenard itself. I know Kardeth. You will crack Pelucir like a nut, take what you want. But you will not stop here. You will not stop until you have laid claim to every mountain pass and goatherder’s hut in Chaumenard.”

“And every rich valley and every ancient book.” Still Riven watched the mage; he spoke courteously, but inflexibly. “Chaumenard is ungoverned. It is full of isolated farmers and wealthy schools where rulers send their children, and villagers who carry their villages around on their backs in the high plateaus.”

“They will fight you.”

“That will be as they choose.”

“If you survive this place.”

The prince’s eyes flickered. He drew breath noiselessly and moved, letting the weariness show in his face, in his sagging shoulders. He unfolded a leather stool for the mage, and sat down himself. He said, surprising the mage, “Atrix Wolfe.”

“Yes. How—”

“I saw you, when my grandfather ruled Kardeth. I was very young. But I never forgot you. The White Wolf of Chaumenard, my grandfather called you, and told us tales of your power when you had gone. He said you were—are—the greatest living mage.”

“I am nearly the oldest,” Atrix murmured, feeling it as he sat.

“I questioned him, for such power seemed invaluable to Kardeth.”

“As a weapon.”

The prince shrugged slightly. “I am what I am. He said that such power among the greatest mages has its clearly formulated restrictions.”

“Experience teaches us restrictions,” the mage reminded him. “They are not dreamed up in some peaceful tower on a mountaintop. If we involved ourselves with war, we would end up fighting each other, and create far more disaster than even you could imagine. Power is not peaceful. But we try to be. The rulers of Pelucir are not peaceful, either,” he added, sliding away from the dream he saw glittering in the prince’s eyes. “This one will turn himself and his household into ghosts before he will surrender to you. I know the Kings of Pelucir. Go home.”

“And you know the warriors of Kardeth.” There was an edge to the prince’s voice. “We do not retreat.”

“Your warriors are battling inhuman things. Pain. Hunger. Madness. Winter itself. Things without faces and without mercy.”

“So is Pelucir.”

“I know.”

“They loosed their hunting hounds two days ago. The hounds howled with hunger all night long within the walls. So.” His hands closed, tightened. “Now they roam at night in my camp; they scavenge with the carrion crows. Among my dead. I will outwait winter itself to outwait the King of Pelucir. And then, in spring, I will march through the greening mountains of Chaumenard.”

“Spring,” Atrix warned, “is another time, another world. In this world, you are trapped in the iron heart of winter, as surely as you have trapped the King of Pelucir, and unless you want to turn into an army of wraiths haunting this field, you must go back to Kardeth. There is no honor for you here. And therefore no dishonor in retreat.”

“I will see spring in Chaumenard.” The prince seemed to see it then: the green world lying in memory, in wait, just beyond eyesight. His eyes focused again on Atrix Wolfe, the fierce and desperate dream still in them. “And the King of Pelucir will live to see it here. And so will his wife, and his heir and his unborn child. If.”

“If.”

“If you help me.”

*

Patricia A. McKillip’s The Book of Atrix Wolfe: 30th Anniversary Special Edition is due to be published by Tachyon Publications in North America and in the UK, on February 25th.