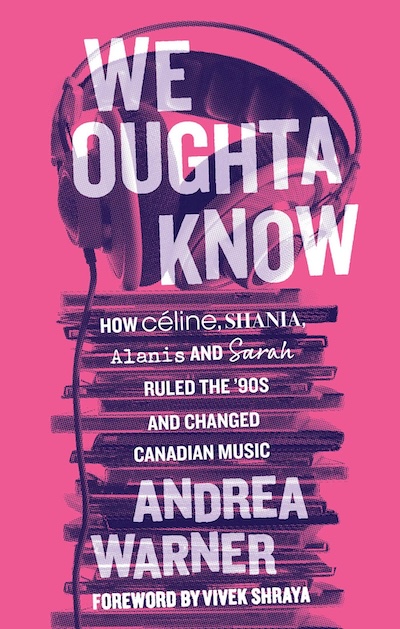

On October 15th, ECW Press is due to publish We Oughta Know by Andrea Warner. The book is an essay collection that examines “How Céline, Shania, Alanis, and Sarah Ruled the ’90s and Changed Music”. To mark the book’s publication, the publisher has allowed CR to share the Introduction. Before we get to the excerpt, though, here is the synopsis:

On October 15th, ECW Press is due to publish We Oughta Know by Andrea Warner. The book is an essay collection that examines “How Céline, Shania, Alanis, and Sarah Ruled the ’90s and Changed Music”. To mark the book’s publication, the publisher has allowed CR to share the Introduction. Before we get to the excerpt, though, here is the synopsis:

A lively collection of essays that re-examines the extraordinary legacies of the four Canadian women who dominated ’90s music and changed the industry forever

Fully revised and updated, with a foreword by Vivek Shraya

In this of-the-moment essay collection, celebrated music journalist Andrea Warner explores the ways in which Céline Dion, Shania Twain, Alanis Morissette, and Sarah McLachlan became legit global superstars and revolutionized ’90s music. In an era when male-fronted musical acts were given magazine covers, Grammys and Junos, and serious critical consideration, these four women were reduced, mocked, and disparaged by the media and became pop culture jokes even as their recordings were demolishing sales records. The world is now reconsidering the treatment and reputations of key women in ’90s entertainment, and We Oughta Know is a crucial part of that conversation.

With empathy, humor, and reflections on her own teenaged perceptions of Céline, Shania, Alanis, and Sarah, Warner offers us a new perspective on the music and legacies of the four Canadian women who dominated the ’90s airwaves and influenced an entire generation of current-day popstars with their voices, fashion, and advocacy.

*

INTRODUCTION

One of my favourite pieces of musical trivia is this: in Canada, up until 2015 at least, Céline Dion was bigger than the Beatles. So were Alanis Morissette, Shania Twain, and Sarah McLachlan. In fact, according to the 2010 Nielsen SoundScan, of the ten best-selling artists in Canada, only five were Canadian and all five were women. Céline Dion was first, then Morissette and Twain, with McLachlan in sixth. Diana Krall was tenth. The Beatles made an underwhelming appearance at number seven.

This chart still reflects a couple of major truths: there were only five Canadians on the list of best-selling artists in Canada. The top four — Dion, Morissette, Twain, and McLachlan — all burst into prominence during a five-year window from 1993 to 1997. Suddenly an impressive statistic becomes a holy shit one. How did these four wildly different artists have such a chokehold on the charts and the culture that they not only changed the gender dynamics of the music industry but also changed music itself?

Yes, of course, the ’90s were a different time. Much to the chagrin of audio purists, people began to embrace CDs over vinyl records and cassette tapes. It was a glorious transition for the ashen-eared non-audiophiles, even while purists resisted, eventually resurrecting vinyl and cassettes. The decade was the final heyday of physical record sales before the bottom fell out in the aughts with file sharing and streaming. But even considering the music industry’s drastic changes, would the average person ever have guessed that four women — Canadian women — were among the best-selling artists in Canada? For example, when critics talked about famous, mainstream Canadian musicians and acts in 2010, masculine acts like Nickelback, Drake, and Michael Bublé typically got priority. Almost fifteen years later, it’s now the Weeknd, Justin Bieber, and, well, Drake is still holding on. It’s a fascinating, exciting, inspiring thing to think that amidst all the bullshit sexism — in the music industry and in the world — these women defied the odds, their critics, and the general consensus that rock ’n’ roll is a man’s space to succeed. Consider that as recently as 2023, Rolling Stone magazine founder Jann Wenner went on the record with the New York Times and declared that his new book, The Masters, did not include any women or Black artists because they “didn’t articulate” at the “intellectual level” of their white male peers.1

So. Many. Questions. About Wenner’s racist, sexist nonsense, and also about how, in the face of prevailing, gate-keeping attitudes like his, Dion, Twain, Morissette, and McLachlan became the big four in Canadian music? What’s the Venn diagram shared by a grande dame of ballads, a country-pop queen, a hissing alt-rock viper, and an angelic folkie? Is Canada a secret feminist wonderland or a hothouse of terrible taste where emotions are easily, voluntarily manipulated? What was it about 1993 to 1997, my prime teenage years (fourteen to eighteen years old), that made it possible for this particular confluence of events? I hated Dion and Twain when I was a teenager. The cheesy sincerity, skimpy outfits, and simpering “love is everything” mantras were an affront to the sarcastic, smarty, arty persona I was trying to cultivate. How the hell did I get to the point where I wanted to write a book that included them and their perky, earnest superstardom? I was team Morissette and McLachlan forever; how did I get so soft? How did we get here?

It’s as if Canada took the essence of the Riot Grrrl movement — made famous in the early ’90s by unrepentant feminist bands like Bratmobile, Bikini Kill, and 7 Year Bitch — and put it through some kind of sanitized metamorphosis. Riot Grrrl’s third-wave radical feminism was political, punk, and DIY. The prominence of Dion, Twain, Morissette, and McLachlan was like a triple distillation — cannibalization, commodification, and gentrification — of Riot Grrrl’s ethos applied across four totally different genres of music. Their success wasn’t antithetical exactly, but it illustrated the spectrum of influence women were having across music in the ’90s and how the razor-sharp edge of the Riot Grrrls could be softened, monetized, and sold in huge numbers. The sheer force of Dion’s, Twain’s, Morissette’s, and McLachlan’s international impact was a bizarre show of strength on Canada’s part, completely unheard of and unique in terms of dominating mainstream music charts, that ultimately ushered in a new era of music in this country.

It’s time to pay tribute and dig a little deeper into the hows, whys, and WTFs of those five years. In 2014, when I began writing about these four women, we had put too much distance between ourselves, their music, and the cultural context they had to navigate, leaning too heavily on scorn, ridicule, and mockery. We’ve started to make amends over the last decade, but there’s still more work to be done.

I know from experience. I spent years giving side-eye to Dion and Twain, instead of identifying and recognizing their achievements in real time. I diminished and demeaned them without considering what that stripped from me in the process, what narratives I was reinforcing, and how I had unintentionally internalized systemic sexism and misogyny. I was a tool of the patriarchy. What a mindfuck.

All four women deserve so much more credit than they were ever given. That doesn’t mean every song was great or even good, but what they did between 1993 and 1997 deserves critical examination and exploration. And not just the music, but the climate as well; there was sexism, misogyny and ageism spilling out in deliberate and casual ways from every corner of the media — from critics to DJs and VJs to music programmers — all clutching their pearls while the politics of feminism was spreading everywhere. The debate was as loud and furious then as it is now, albeit in diffe ent ways. (The broader strokes of feminism were once the focus of mainstream conversation whereas now there’s more interest in intersectionality, trans-inclusive feminism, and confronting the ways in which white feminists uphold white supremacy.) But for five years, Dion, Twain, Morissette, and McLachlan, four larger-than-life, hugely successful women, were everything and were driving feminist conversation, whether they ever intended to or not. It was a monumental time in Canadian pop culture, and it changed the music industry here and abroad. It also changed me.

It’s been ten years since I wrote the first iteration of this book, and the ’90s revival is still going strong. In part, it has manifested as an ongoing and never-ending series of exercises: identifying entrenched sexism and misogyny and unpacking how both shaped culture and taste; confronting and identifying institutional and systemic barriers as well as personal complicity and accountability; and envisioning and enacting a more inclusive and intersectional feminism. It’s exhausting, and in a lot of ways, I’m angrier than I’ve ever been, yet my rage is more focused because I’m better equipped and empowered to name it. And the credit is due to the extraordinary folks who are coming up behind me: younger intersectional feminists who are often racialized, queer, gender fluid, and/or nonbinary, who loudly name and call out transphobia, gendered violence, racism, sexism, misogyny, homophobia, white supremacy, bullying, ableism, fatphobia, and other toxic behaviours for what they are. No euphemisms, no excuses, no tolerance for inflicting harm or wielding power in oppressive, punishing ways.

I am thrilled and fascinated by the recent desire and demand for media, moguls, fans, and haters alike to reconsider what we think we know about infamous and invisible women; to consider who has been vilified or erased or exploited and/or all of the above. The focus on the ’90s isn’t surprising, as it marked a turning point in media: the internet was in its infancy, the massive magazine collapse of the early to mid-2000s was on the other side of a looming Y2K panic, and “feminism” was less a shorthand for equality and empowerment and more a code that was conflated with hating men and girl power. Queen Latifah, TLC, Hole, Liz Phair, Alanis Morissette, Spice Girls, Britney Spears, Avril Lavigne — this is just a cursory overview of the women artists who continue to spark conversation about the ways in which feminism was represented, contested, and refuted in ’90s music. Most were scrutinized and exploited in different ways and to different extents, whereas others were essentially ignored, erased, and discounted. Every which way, it was rarely about the music and much more about their bodies, looks, sexuality, dating history, and policing their attitudes, personalities, and choices. This current reckoning of women reclaiming their agency, telling their own stories, and correcting the skewed, sexist, misogynist, racist, ableist record has been a long time coming. It’s a powerful and important counternarrative. But it doesn’t make up for what women artists lived through all those years ago.

In the last decade, Twain, Dion, Morissette, and McLachlan have all found themselves back in the spotlight. Twain launched a massive comeback with 2017’s Now, her first album of new material since 2002’s Up!, and she was the subject of a 2022 documentary, Not Just a Girl. Dion’s husband and long-time manager, René Angélil, died in 2016, and in 2022, she revealed she’d been diagnosed with stiff-person syndrome, a serious neurological condition. (She also finally became an actual fashion icon instead of just an aspirational one, through her work with stylist Law Roach). Morissette was the subject of a documentary as well (Jagged) but publicly disavowed it before its release, while also helping turn Jagged Little Pill into a Tony Award– winning Broadway musical and launching a massive Jagged Little Pill anniversary tour. McLachlan and Lilith Fair became the subjects of a sprawling Vanity Fair oral history. All four are taking back what was stripped from them, and I don’t know if these cultural reappraisals and reassessments are necessarily meaningful to them personally, but they’re vital to me and to many other fans in Canada and beyond. I also think it’s crucial for their music catalogue to have a more just reassessment of the importance of their songs, for the artists facing similar scrutiny, hostility, and scorn now, and for everyone who directly confronts the ongoing damage of the patriarchy, including those of us who have internalized it and are trying to unlearn it.

I used to think that I was sixty-two percent Jagged Little Pill era Alanis and thirty-eight percent pre-Surfacing Sarah, but I have to admit that all four women carved out holes in my bones and settled into the marrow. When four women are such visible, inescapable forces in the pop culture of your youth, when you see four women shake the music industry from its male-dominated grip, when you realize that all four of them did this in their late teens to their mid-twenties — just a few years ahead of yourself in your mid-teens — their influence on you is like sunken treasure at the bottom of the ocean. It can take weeks, months, years, even decades before a true understanding of why you care so much comes, gloriously, to the surface.

1. David Marchese, “Jann Wenner Defends His Legacy, and His Generation’s,” New York Times, September 15, 2023

*

Andrea Warner’s We Oughta Know is due to be published by ECW Press on October 15th.