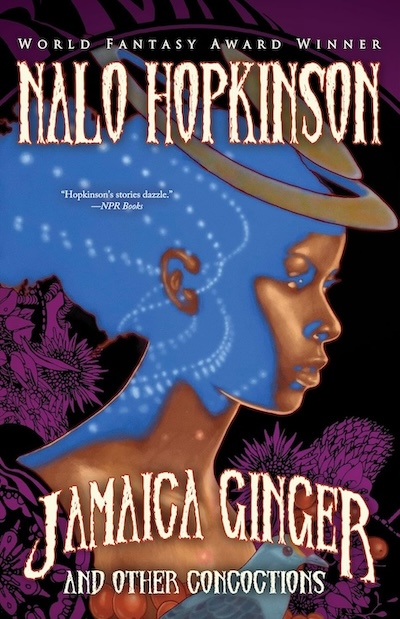

On October 29th, Tachyon Publications are due to publish the new fiction collection by Nalo Hopkinson: Jamaica Ginger and Other Concoctions. To celebrate, Tachyon has provided CR with an excerpt share from one of the stories, “Propagation”! Before we get to that, here’s the synopsis for the collection:

On October 29th, Tachyon Publications are due to publish the new fiction collection by Nalo Hopkinson: Jamaica Ginger and Other Concoctions. To celebrate, Tachyon has provided CR with an excerpt share from one of the stories, “Propagation”! Before we get to that, here’s the synopsis for the collection:

Caribbean-Canadian author Nalo Hopkinson (Brown Girl in the Ring, The Salt Roads, Falling in Love with Hominids) is an internationally renowned storyteller. This long-awaited new collection of her deeply imaginative short fiction offers striking journeys to far-flung futures and fantastical landscapes. Hopkinson is at the peak of her powers, moving effortlessly between art, folklore, science, and magic.

Hailed by the Los Angeles Times as having “an imagination that most of us would kill for,” Nalo Hopkinson and her Afro-Caribbean, Canadian, and American influences shine in truly unique stories that are gorgeously strange, inventively subversive, and vividly beautiful. In her first stories since 2015, a woman and her cyborg pig eke out a living in a future waterworld; two scientists contemplate the cavernous remains of an alien lifeform; and an artist creates nanotechnology that asserts Blackness where it is least welcome.

The author has also written a short introduction to the story, included below before the story itself.

*

NOTE: This introduction was written before the news came out about Neil Gaiman’s predatory and abusive relationships with many women. Before I learned about it, Neil was someone I considered a friend. I regret I can’t change my past ignorance. I won’t try to erase the evidence of it here, though nowadays, just seeing his name in writing makes me furious.

Some years ago, author Neil Gaiman was tapped by TED (the organization that produces the TED talks) to curate an evening of storytelling at its annual conference in Vancouver, Canada, with Amanda Palmer as MC. The authors who said yes to Neil’s invitation were Sofia Samatar, Monica Byrne, Nnedi Okorafor, and me. TED wanted optimistic science fiction stories from us. I often find that a difficult order, because I vaguely resent being constrained to be “positive.” So the story was fighting me the whole way. As I was about to hop on the plane from Southern California to Vancouver to give the reading that same evening, it occurred to me that I hadn’t confirmed the validity of the scientific premise of my story. I quickly left a message for an old friend of mine to whom I often turn when it’s a question of biology. I arrived at my Vancouver hotel a few hours later to a message from him. As I’d feared, the science not only didn’t but couldn’t work. I had mere hours to do something. I went blank with panic for a few seconds, then I implored my outside-the-box ADHD brain to work its magic for me.

It did. It reminded me why I very much wanted the story to turn out the way it did, why it felt vital to locate its hope for future possibility in the experience of a poor, young, inner city Black girl from the Caribbean. It reminded me that strict science fictional protocols and narratives that presume cultural ownership of the means of technological progress often don’t quite fit stories told from the perspective of marginalized communities. (If only because the realities of our lives and histories under colonialism are so beyond belief that sometimes we needs must have recourse to the metonymizing possibilities of the fantastic in order to tell our stories.) It reminded me that in order for us to have futures, the impossible needs to be made possible. It reminded me that that’s what science fiction does. It reminded me that speculative fiction often plays fast and loose with genre norms. And it reminded me that the story needed to serve me, not the other way around. I could mess with form as much as I wished in order to tell my story.

I took a deep breath and began reinventing the piece. Halfway through, Neil called my hotel room. As if to prove that he knows me better than I think, he apprehensively asked me whether my piece would be ready. (Or maybe he’s just psychic. God, I hope not.) I promised him that it would. Because by then, I’d begun to get the feeling that, incredibly, it would, with only minutes to spare until I had to leave for the event.

What I came up with was part fiction, part essay, all performance piece. It was a largely fantastical examination of scientific progress and what it needs to do to benefit the whole world, not just certain populations.

When I gave the reading, the audience seemed to very much enjoy it. Neil pronounced himself satisfied. He understood what the story was trying to do. And I was relieved.

Here’s the rub: when you read this story as words on a page, it doesn’t gel. I’ve had people both read it and then see me do it. For them, it only clicks when delivered as a piece of performative speculative storytelling, with commentary, told in multiple, code-switching registers. For me, that means it returns to my roots in Caribbean orature. And I’m happy with that. Very happy.

Just don’t tell Neil I was still writing it when he called.

PROPAGATION: A SHORT STORY

Once upon a time one fore day morning, a loud bang wake Kinitra and her young brother Purvis from off them mash-up mattress on the floor in the corner of the one room where Kinitra and Purvis and Ma and Grandma all of them living.

Grandma was sitting in the rocking chair by the window. Same place she was sitting when Kinitra go to bed last night.

The noise make Ma sit up in her and Grandma’s bed. The white nightie and the darkness in the room make Ma brown skin look black, true black. She tell Purvis and Judith to hush them bloodcloth mouth is probably just them blasted shottas again with them born-fi-dead stupidness like the battle them was waging with the rasscloth police all through the dungle last night wasn’t enough for them, ee?

Grandma say is not shottas, daughter. Been sitting here all night, you know how the old bones don’t need plenty rest. Nobody outside. Shottas and all gone to bed hours ago.

Fore day morning light coming in the window was enough for Kinitra to see Grandma look at her, hard. Not enough to see what kind of mind Grandma was examining her with. Grandma know her granddaughter good, for Kinitra had a suspicion the noise that just shake the whole of the dungle was her fault.

Ma say, “Me never know gun to sound like that. Just one boom, and loud so?”

Purvis had already run straight to Grandma. She pull him onto her wide lap. She lie his head against her breast. Time was, that would have been Kinitra taking comfort in her grandmother’s arms. But she was too big now. Time to take action instead.

There was another sound, soft on the tinning roof over them heads. “Is rain that?” Ma asked.

“In dry season?” Grandma reply.

Little Purvis gasp, him y’eye-them big as him look out the window. “Feathers!”

Grandma screw up her eyes to try to see is what him a-chat bout. She couldn’t see too good any more. Old bones, old eyes.

Kinitra ongle asking herself what went wrong. Bird feathers? Couldn’t be. So she too get out of bed and go over to the window. Not Ma. Ma all the time saved her strength for the necessaries; walking to work at the factory in the morning before bus start run, working at the factory, taking the bus home from the factory come evening, doing the same thing the next day, six days a week.

Kinitra look out the window. Wasn’t feathers raining from the sky, landing pop-pop-pop on the roof, filling the air with the warm smell of—

“Popcorn!” Kinitra’s heart swell up in her throat. She didn’t dare laugh, for she wasn’t ready yet to confess what she had been getting up to. She just watch the white fluff drifting down onto the dungle. Popcorn. Like Grandma make sometimes, shaking the kernels in the big pot on the stove with the kibber shut tight. Hot popcorn cook with coconut oil and afterwards some salt and a little pat of margarine on top afterwards. Butter when they could afford it.

Brother Purvis looked up at Kinitra. “Popcorn? Heaven popcorn?”

Grandma laugh when she hear that. She gie Purvis a big kiss on the cheek for being a clever boy. Ma even get out of her bed to come see the heaven corn. Couple-few popcorns had landed on the window ledge. Ma picked one up and sniff it. She frown. Put a single popcorn onto her tongue, like a communion wafer. Kinitra hold her breath, ‘fraid say her food would make her ma sick. She was just about to beg Ma to spit the popcorn out, but Ma swallow. She smile. “It good.”

Grandma try it too, but she ongle say, “Huh.” You know the way grandmothers stay. Kinitra had to squabble with Purvis for the pieces remaining on the window sill. Purvis ask Ma if he could go outside and eat more. Ma say shottas could still be dey-bout, but she let Purvis open the door little way and stick his hand out the door bottom and collect some handsful of popcorn. Ma inspect each piece and throw ‘way any piece that had even a speck of dungle dirt on it.

As the sun was coming up, for a few minutes the ground of the dungle was white like a duppy-dead, instead of warm red dirt and the grey of pavement and mash-up asphalt road and little strokes of living green swips swips all over the place of weeds growing through the broken pavement.

Kinitra had her business to see to. She was dying to get up onto the roof, but she couldn’t do it under Ma’s johncrow eye, quick to spy out any mischief. So Kinitra say, “Grandma, what time it is?”

Grandma pick up her cell phone from the window sill. “Six thirty-two.” Then she say to Ma, “Carol, nuh time for you to go to work?” Then she wink at Kinitra. That’s how Kinitra know that Grandma’s mind was favouring her in this business.

Ma grumble ‘bout how toil never done. But she onned the lights. She went in the bathroom and cleaned herself with the water remaining in the bathtub. She put on her work clothes. She fill a yogurt container with some leftover peas and rice and stew chicken from the fridge. She remind Purvis and Kinitra of their Saturday chores: Purvis to fetch water from the standpipe out in the road so Kinitra could cook and mop the floor and so the women of the house could bathe decent in the tub, not half-naked by the standpipe like the dungle men and boys.

It was sun-up and by now, the whole dungle knew is what a-gwan, how the heavens open up and rain food like manna down ‘pon them. It was commotion in the streets. People fetching up popcorn in bucket and cup. And the wonderful smell, Lawd Jesus. The smell of hot coconut oil and exploded corn kernels. The whole time Ma giving them instructions, Purvis sidling over to the door, ready to run get his share. Kinitra ongle fighting herself not to look up at the ceiling. The big bang, it come from their roof. She had to go check on the Mole. If it break, she nah know how to get another one.

Finally, finally Ma leave for work. Purvis dash outside with their bucket. Grandma shout after him that he best fill that bucket up with clean water, not snacks from off the ground. Then she turn to Kinitra. “Is you do this?”

“I think so. I didn’t mean for it to turn out so. I don’t know what happen.”

“Well go then, nuh?” Grandma waved Kinitra towards the stairs behind the apartment. “Go see to your precious assembler.”

You haffe understand, Kinitra’s Ma had plenty reason not to check for the gangs and their shottas. She could lose her boy pickney to them any day now, and her girl pickney in worse ways. Already lost her baby brother to them ten years previous. Kinitra’s Uncle Selvon was still living, but some of the things he had to do to stay that way, he wouldn’t or couldn’t discuss.

Time was, drug trade was a big—Uncle would say “income stream” in gang business. But when it get to where any puss or dog could build them own 3D printer and print out as much cocaine as them want, well, the gangs had to diversify. Uncle Selvon’s gang went into politics—what Ma would call “politricks”—and Uncle Selvon give Kinitra them old 3D printer, cause he know say him young niece like feh passa-passa with all kind of machine.

*

Nalo Hopkinson’s Jamaica Ginger and Other Concoctions is due to be published by Tachyon Publications in North America and in the UK, on October 29th.