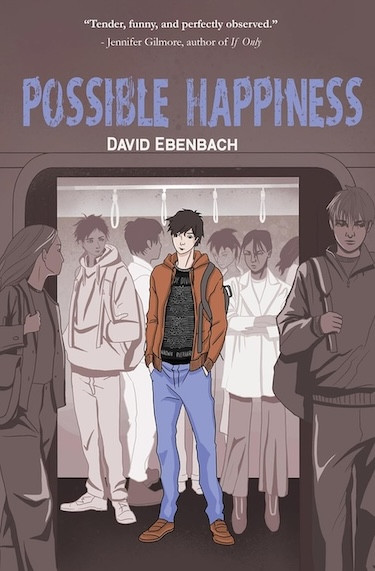

Today we have an annotated excerpt from David Ebenbach‘s latest novel, Possible Happiness. Published by Fitzroy Books, here’s the synopsis:

Today we have an annotated excerpt from David Ebenbach‘s latest novel, Possible Happiness. Published by Fitzroy Books, here’s the synopsis:

Eleventh-grader Jacob Wasserman is just trying to get by. Under the radar, he spends his weekends at home by himself, leaning on TV and video games to distract himself from the weight — these days we would call it depression — inside him. But he’ s secretly got a quirky sense of humor, and, when he starts letting it show, he finally gets noticed. In fact, before he knows it, Jacob’ s ability to keep people entertained has drawn him into a full-time social life, complete with a circle of friends, parties, and even a girlfriend. But is this newfound acceptance enough to unlock meaningful well-being? Is this entertainer even the real Jacob?

Possible Happiness is a funny and tender coming-of-age story about developing the courage to face and understand yourself.

Without further ado, I shall pass it over to David…

*

Thanks so much to Stefan for hosting me and an excerpt from my new novel, Possible Happiness! This excerpt is very near the beginning of the book. Basically, Jacob (the main character) is a kid growing up in Philadelphia in the late 1980s, flying under the radar at his high school. But he’s got a sense of humor that wants to show itself. And so here goes:

Anyway, so one day — it was late September — he was in Advanced History, listening to Mr. Nowacki talk about pre-revolutionary America. Jacob couldn’t decide whether Mr. Nowacki was a cool guy or not. He owned a sportscar, which you could sometimes get him to talk about in class, and he was informal with the students, in the sense that he would call on kids with lines like, “Okay, smart guy, whaddaya got?” and would respond to wrong answers with “No, but thanks for playing,” and he dressed like he was actually living in the late 1980s, whereas a lot of the other teachers were practically still in the 70s. Jacob liked him, but did sometimes wonder if Mr. Nowacki was cool or just trying to be cool. Regardless, he was friendly toward Jacob, and on this particular day when he asked, “Who can tell me who was living in the colonies at this time?” Jacob actually, without pausing to think about it, called out what had popped into his head. “The colonists!” he said. Immediately afterward Jacob felt his face burning — he was as shocked as a housecat thrust suddenly outdoors — but Mr. Nowacki just twitched his dark moustache and said, “Thank you, Shecky. Shecky Greene, everybody.”

Jacob, still burning, did then give Mr. Nowacki the answer he was looking for, which was people who had fled Europe to escape religious persecution, and Mr. Nowacki said, “Okay — I guess his brain still works,” and things got back on track.

I did have a teacher like Mr. Nowacki back in high school—he taught Physics. With the benefit of hindsight I can say that he was more or less cool. This is one of the many, many, many autobiographical elements in this novel.

But after class, in the swarming hallway, while Jacob went over that moment again and again — he had a habit of second-guessing himself, except that he usually couldn’t stop once he’d started and so it was more like frenetic fifteenth-guessing or hundredth-guessing or nine-hundredth guessing — someone called Jacob’s name. Jacob turned and saw Eric Strudwick’s head of feathered red hair bobbing up like a balloon over everyone else; Eric was already more than six feet tall at age sixteen. He knew Eric, a little. The two of them were in the same history class, which was not the first class they’d been in together, and they both lived in West Philadelphia, too, as relatively rare white people, and in fact Eric was also similar in that he hadn’t been discovered in the high school universe yet, either, though Jacob suspected that more people noticed Eric, at least because of the tallness and the red hair. In any case, despite all the similarities, for some reason they had never really hung out, aside from a couple of times in middle school. Eric and his family had been away — Canada, maybe? — for a couple of years in there, so maybe that was part of it.

Eric closed the distance through the crowd now and said, “Jake,” again, extending his hand to be shaken. “You are hilarious.”

Small thing here: Eric, and all of the other friends that Jacob’s about to make, will call him “Jake,” which is not something he ever calls himself. I wanted to integrate a subtle sign that these new friends, as nice as they all are, don’t quite see the main character for who he really is.

It felt a little strange and formal, and Jacob had to wonder if he was being teased — he felt really, really stupid about his joke — but it didn’t seem like it from Eric’s face, and Jacob shook his hand. “Thanks,” he said, almost like a question. The crowd swirled past them, everyone on their way to their next classes.

“How are you doing, man?” Eric said. “Which way are you going?”

Jacob, who didn’t know what was going on, pointed in the direction he was headed, and the two of them started walking together. Everywhere around them were other people, going various places loudly.

I keep bringing up how crowded these hallways are, and that’s because of what I call the “thermostat effect”: you have to remind the reader what the environment is like if that environment is likely very different from the reader’s environment. For example, if you want readers to feel colder than where they’re reading, you have to talk frequently about the cold, or the readers will forget and revert to feeling as warm as the rooms they’re in. And the same goes when it’s raining in your book, or crowded, or an alien planet. Setting, in other words, is a thing that has to be renewed.

“That class is pretty cool,” Eric said, thumbing back in the direction of Mr. Nowacki’s room.

“Yeah,” Jacob said. So that was a vote for Mr. Nowacki being cool, which Jacob noted. “I like it.”

“Listen,” Eric said, with some intensity. Jacob remembered that, even back in middle school, the energy level always seemed to go up around Eric. “I’m having a party in two weeks,” he said. Still in motion, he flipped his bookbag forward so he could open it and pull out a manila folder, from which he extracted a crisp flier. “Music, dancing. You should come,” he said, handing the sheet to Jacob.

Jacob didn’t really see the flier at first — he was taking his time processing the idea that he was being invited to a party, and not like a birthday party but like a party party. “Wow, great,” he found himself saying. “Totally.” And then he checked the date, as though there was any chance he was going to be busy then. The flier gave the date, and times, too — 8pm to midnight — over the words Fresh Dance Party! The whole thing had been handwritten and Xeroxed. “Thanks. I can totally do this.”

I am definitely trying to signal — with the manila folder, the crisp flier, the end time, and the slang, that Eric is not exactly one of the cool kids.

“Great,” Eric said, settling his backpack on his back and shaking Jacob’s hand again. “And feel free to invite anybody else you want, too, if they’re cool.”

“Okay, sure,” Jacob said. He was looking at Eric’s extreme, almost translucent whiteness and his preppy button-down shirt and his jeans rolled up, and thinking that probably Leron and the guys wouldn’t be interested in this party.

Jacob’s current friends — not very close friends, but kids he rides the subway home with — are also from West Philly, and they’re Black. The friends that Jacob is about to make, on the other hand, are all white. The way that people group socially around race is a recurring note and a source of tension in Possible Happiness.

“Especially girls,” Eric said.

“Definitely,” Jacob said.

“If they’re cool.”

Jacob nodded as if to say, I know exactly what you’re talking about.

When I started out as a writer, I was deadly serious all the time. I figured that the only way to talk meaningfully about the world was to take it all very grimly. Now I realize that humor is a great way to explore serious things. Not only does humor lure the reader in, but it also makes the sad moments more intense by contrast.

Then they walked on a little further, down the big hallway now, which was just swarming with people. The rumor was that Central’s administration was overenrolling the school so that they could make an argument for a new science wing. Jacob wasn’t sure that kids would actually have access to that kind of inside information, but it was a plausible explanation.

And setting isn’t just setting. Now the setting is creating some space between Jacob and the adult world, but also leaving him with some doubts about kids his own age.

“Hey — have you ever seen the movie Evil Dead?” Eric said now.

Jacob had not. He didn’t usually go to see things.

This is a hint of the serious stuff that’s at the center of the book: Jacob’s inertia, which these days we would call depression.

“That movie is crazy. I’ve gotta tell you all about it,” he said. “I’m turning here.”

And before Jacob knew it, Eric had turned down another hallway — the school was shaped like a capital E and this was the middle line of the E. Jacob stutter-stepped, which made someone crash into him from behind. “Come on, man,” the person said. And Jacob’s face went hot and he apologized a few times and got himself moving again, off to English class, his thoughts all over the place, holding the flier uncertainly in his hand.

*

David Ebenbach’s Possible Happiness is due to be published by Fitzroy Books on September 10th, in North America and in the UK.

Also on CR: Interview with David Ebenbach (2021); Excerpt from How to Mars

Follow the Author: Website, Goodreads, Instagram, TikTok