I ran a workshop at a convention last year on world building. It would be accurate to say that it was a section of a world building workshop I’ve been running for several years, because whenever I set out a bunch of topics, I generally manage about a third of them before we get hung up on something, and the rest never gets touched.

I ran a workshop at a convention last year on world building. It would be accurate to say that it was a section of a world building workshop I’ve been running for several years, because whenever I set out a bunch of topics, I generally manage about a third of them before we get hung up on something, and the rest never gets touched.

This time round, I dived into social conventions: governments, class systems, and then we hit the brick wall of religion and that is where the discussion firmly stayed.

This recurred to me while editing The Tiger and the Wolf because one of the main ways this series differs from Shadows of the Apt is the spiritual dimension. The insect-kinden of Shadows are aware of the concept of gods but have no truck with the idea. Their attitude to the numinous (those who can even conceive of it) is as something to master and control, not appease or worship. For Tiger I wanted to explore a culture that lived in constant dialogue with the spiritual. The various tribes’ ability to shapeshift is the cornerstone of a religion that, though it finds different expressions in different tribes, links them all together with a common cosmology.

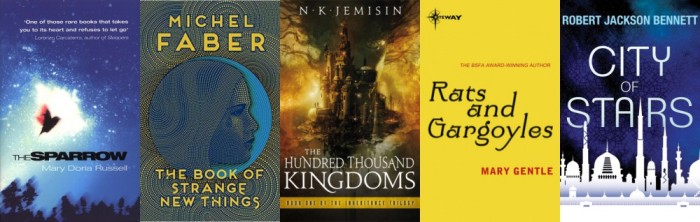

Strange gods are a fantasy staple, but one perhaps honoured more in the breach than the observance. Look at your traditional D&D party – a warrior, a rogue, a ranger, a wizard and a cleric. But the weird thing is that, of all those classes, D&D seems to have spun the cleric out of whole cloth rather than from literary precedent. SF has some fairly explicit looks at religion and people of faith, Russell’s The Sparrow or Faber’s The Book of Strange New Things to name but two, but fantasy fiction tends to tiptoe a bit more around the subject. It helps that SF set in our future can use our real religions and sit happily in that indeterminate region that faith occupies. In a secondary world the axioms are at the author’s absolute discretion, which leaves the big question of where you fit something as large as God or gods?

You can, of course, have the gods as actual characters present in the narrative, as in Jemisin’s The Hundred Thousand Kingdoms. There, the gods are vast and powerful but, being physically present, they are political forces in their own right. Religion and faith are beside the point when the family squabbles of the pantheon are happening in the next room. Gentle’s Rats and Gargoyles removes the divine one step further – present but profoundly inscrutable, requiring a priesthood to manage and interpret them. Bennett’s City of Stairs has a world where the gods were very real and present, and then were destroyed. The world under divine rule was wondrous and terrifying and strange, but at the book’s start we’re left with a world with religions built from bitter nostalgia and inextricably entangled with ethnic identity and political agenda.

Other settings with actual active gods tend to shrink them down to something less omnipotent and sometimes barely potent at all. Howard’s Conan stories are full of otherworldly entities posing as gods, but they tend to be demonic and their empowered ‘priests’ are generally evil magicians. Other named gods are seldom shown as having any real existence – the supremely disinterested Crom is a good example of a god that probably doesn’t exist, but wouldn’t be any more visible if he did. Settings influenced by Howard and the other pulp writers tend towards loose pantheons of numerous gods of limited purview. Leiber’s Lankhmar has plenty of narrow specialist gods that provide the exemplars both for D&D pantheons and Pratchett’s Discworld deities. Erikson’s gods in his Malazan books are a major force in the plot, but represent one end of a continuum of power that mortals are most certainly able to climb up, and are explicitly at the mercy of their mortal worshippers. Moorcock’s Elric books have a similar set of deities, destined to be overthrown by mortals.

Of course, you can have the religions without the gods. There are plenty of fantasy worlds where the clear implication is that religions are solely a social construct (as I read it). The Kargish religion in le Guin’s Earthsea, the Church of the Seven in Martin’s Ice and Fire and other religions from Abercrombie, Brett and Gemmell are all from this mould. The religions thus depicted are also often portrayed negatively, either venal and corrupt or fanatical and persecuting.

On the subject of GRRM’s Ice and Fire, one of the setting’s strengths is the range of different beliefs across Westeros and the wider world, a variety not often seen in fantasy. There is little suggestion that the gods followed truly exist, except for the one that has bona fide dead-resurrecting clerics on the staff, though where that power actually comes from is another matter…

The beliefs in the world of The Tiger and the Wolf link animal shapes with human souls. Maniye, the heroine, has two shapes and is torn between two natures caught in a war between two very adversarial gods. Unlike the mechanical, rationalist insect-kinden, the way the shapeshifters see their world is entirely filtered through their beliefs. This was a challenge for me: I’m definitely in the rationalist camp myself and it would have been very easy to take a rather patronising view of it all, leaving whatever the characters chose to believe as just various shades of wrong. The far end of the spectrum would be to have actual and unarguable divine representation. Whether outright false or indisputably true, either pole precludes writing about a society where belief is important. If I used my author fiat to weigh in for the either the real or unreal, it would trivialise the perspective of the characters themselves. It is possible that the various encounters with the numinous and spiritual in the book are solely subjective, but that’s beside the point. The characters believe absolutely in their view of the world, they have a variety of personal relationships with their deities and their understandings of the spiritual underlie every decision they make. Because the narrative is told through those characters, the world they believe in is as important as, and constantly overlapping with, the physical world they move through.

*

Also on CR: Interview with Adrian Tchaikovsky; Guest Posts on “Nine Books, Six Years, One Stenwold Maker”, “The Art of Gunsmithing — Writing Guns of the Dawn“; an Excerpt from Guns of the Dawn; Reviews of Guns of the Dawn, Empire in Black & Gold and The Bloody Deluge

Adrian Tchaikovsky’s The Tiger and the Wolf is published in the UK by Tor, and is out now. For more on his writing and novels, be sure to check out his website, and follow him on Twitter and Goodreads. Adrian is also the author of the epic Shadows of the Apt fantasy series, and the superb Guns of the Dawn (fantasy) and Children of Time (sci-fi).

[…] Stenwold Maker“, “Art of Gunsmithing — Writing Guns of the Dawn” and “Looking for God in Melnibone Places: Fantasy & Religion“; Excerpt from Guns of the Dawn; Reviews of Empire in Black & Gold, The Bloody […]

LikeLike

[…] One Stenwold Maker”, “The Art of Gunsmithing — Writing Guns of the Dawn“, “Looking for God in Melnibone Places: Fantasy & Religion” and “Eye of the Spider”; Excerpt from Guns of the Dawn; Reviews of Empire in Black […]

LikeLike

[…] Six Years, One Stenwold Maker”, “The Art of Gunsmithing — Writing Guns of the Dawn”, “Looking for God in Melnibone Places: Fantasy & Religion” and “Eye of the Spider”; Excerpt from Guns of the Dawn; Reviews of Empire in Black & […]

LikeLike

[…] One Stenwold Maker”, “The Art of Gunsmithing — Writing Guns of the Dawn“, “Looking for God in Melnibone Places : Fantasy and Religion”, “Eye of the Spider”; Excerpt from Guns of the […]

LikeLike

[…] One Stenwold Maker”, “The Art of Gunsmithing — Writing Guns of the Dawn“, “Looking for God in Melnibone Places” and “Eye of the Spider”; Excerpt from Guns of the Dawn; Reviews of Empire in Black […]

LikeLike

[…] Years, One Stenwold Maker”, “The Art of Gunsmithing – Writing Guns of the Dawn“, “Looking for God in Melnibone Places — Fantasy and Religion”, “Eye of the Spider”; Excerpt from Guns of the […]

LikeLike

[…] on “Nine Books, Six Years, One Stenwold Maker”, “The Art of Gunsmithing”, “Looking for God in Melnibone Places”, “Eye of the Spider”; Excerpt from Guns of the Dawn; Reviews of Empire in Black and […]

LikeLike

[…] Adrian Tchaikovsky (2012); Guest Posts on “Nine Books, Six Years, One Stenwold Maker”, “Looking for God in Melnibone Places”, “Eye of the Spider”, and “The Art of Gunsmithing: Writing Guns of the […]

LikeLike

[…] on “Nine Books, Six Years, One Stenwold Maker”, “The Art of Gunsmithing”, “Looking for God in Melnibone Places” and “Eye of the Spider”; Excerpt from Guns of the Dawn; Reviews of Empire in Black […]

LikeLike

[…] One Stenwold Maker”, “The Art of Gunsmithing — Writing Guns of the Dawn“, “Looking for God in Melnibone Places — Fantasy and Religion”, and “Eye of the Spider”; Excerpt from Guns of the Dawn; Reviews of Empire in Black […]

LikeLike

[…] Years, One Stenwold Maker”, “The Art of Gunsmithing: Writing Guns of the Dawn“, “Looking for God in Melnibone Places: Fantasy and Religion”, and “Eye of the Spider”; Excerpt from Guns of the Dawn; Reviews of Empire of Black […]

LikeLike

[…] Books, Six Years, One Stenwold Maker”, “The Art of Gunsmithing: Writing Guns of the Dawn”, “Looking for God in Melnibone Places: Fantasy and Religion”, and “Eye of the Spider”; Excerpt from Guns of the Dawn; Reviews of Empire of Black and […]

LikeLike

[…] Books, Six Years, One Stenwold Maker”, “The Art of Gunsmithing: Writing Guns of the Dawn”, “Looking for God in Melnibone Places: Fantasy and Religion”, and “Eye of the Spider”; Excerpt from Guns of the Dawn; Reviews of Empire of Black and […]

LikeLike

[…] Books, Six Years, One Stenwold Maker”, “The Art of Gunsmithing: Writing Guns of the Dawn”, “Looking for God in Melnibone Places: Fantasy and Religion”, and “Eye of the Spider”; Excerpt from Guns of the Dawn; Reviews of Empire of Black and […]

LikeLike

[…] Books, Six Years, One Stenwold Maker”, “The Art of Gunsmithing: Writing Guns of the Dawn“, “Looking for God in Melnibone Places: Fantasy and Religion”, and “Eye of the Spider”; Excerpt from Guns of the Dawn; Reviews of Empire of Black and […]

LikeLike